Duddon Dragonflies and Damselflies

"DRAGONFLIES AND DAMSELFLIES IN THE UPPER DUDDON AREA" by Chris Arthur, ecologist and volunteer. May 2024

Local ecologist and volunteer at Restoring Hardknott Forest, Chris, has been a big help sharing his time and expertise with our project. He's been particularly helpful with some work on bats. His instagram account always has fascinating photos of some of the rarer and harder to find flora and fauna of the Duddon Valley. Here he has turned his attention to the dragonflies and damselflies found in our area. All photos taken by Chris.

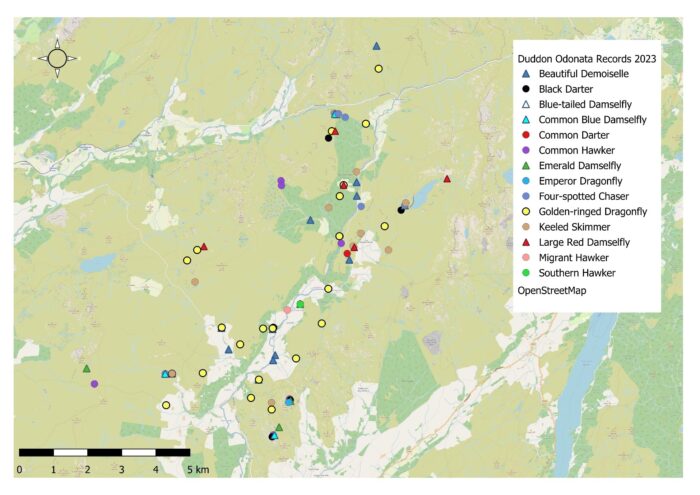

In early 2023 I moved to the Duddon Valley. At around the same time I was undertaking newt surveys at a site in West Cumbria and noticed some dragonfly larvae mooching around the edges of one of the ponds. Being an inquisitive soul, trying to identify the species was high on my agenda; probably broad-bodied chaser (Libellula depressa) was the best I could manage (largely thanks to Cumbria’s resident expert and county recorder for these species). A few weeks later I was lucky enough to catch several of these larvae leaving the ponds and emerging as dragonflies and enabling me to confirm the ID. This spurred me to spend several months exploring the Duddon Valley to check any sign of water shown on the map and see what, if anything, was to be found there. Naturally this included areas within the Restoring Hardknott Forest and broader Upper Duddon Landscape Recovery Project. At the end of the article is a distribution map showing my findings, but it must be noted that not all areas were visited frequently during the season.

The Odonata are predatory insects comprising dragonflies (Anisoptera – unequal wings) and damselflies (Zygoptera – paired wings). Dragonflies are generally larger and stronger fliers, with two different sets of wings which are almost always held horizontally whilst at rest. Damselflies are typically smaller, with two equal pairs of wings which are usually held vertically at rest. Both dragonflies and damselflies are hemimetabolous (ie. there is no pupal stage in their life cycle as there is with butterflies, for example), being aquatic in their larval stage before leaving the waterbody to emerge as adults. As they emerge, the larval casing is left clinging to vegetation around the edge of the pond or stream – this is called the exuvia and can be a perfect shell of the larvae which can be used for identification. Following emergence, odonata take several days to feed up and mature, during which time their colouration may also develop. Dragonflies in particular show clear sexual dimorphism with the males often more conspicuously coloured than the females, though the sexes often look the same shortly after emergence and the variation in colouration can take several days to develop. The adults can be found foraging far from any waterbodies, but will return to them in order to mate, forming a ‘wheel’, before the female lays eggs in (or near) water using her ovipositor and the life cycle continues. Some species develop over the course of a year, though for other species this can take up to 5 years between generations.

The UK has 25 resident species of dragonfly and 17 of damselfly, though it is fairly common for others to migrate from elsewhere in Europe during the summer and autumn. These are most common on the South coast and, unsurprisingly, this is where the greatest diversity of odonata is usually found. There are, however, several species only found in the Scottish Highlands. Falling between these two extremes, the assemblage in Cumbria is less diverse than some other parts of the UK but has seen several species expanding their range into the county in the last few years – most notably a ‘Norfolk’ hawker (Aeshna isoceles) was recorded on the South coast of Cumbria last year (and not a million miles away from the Duddon Valley). See later in the article for the effects of climate change and the risks this poses.

Keeled skimmer (female)

It was a relatively late start for odonata in the Duddon Valley in 2023, with my first record being the 7th May for a single large red damselfly (Pyrrhosoma nymphula) seen emerging on bog-bean at the edge of Nettleslack Bog. My next record isn’t until the end of the month, but then things started to get going properly. Three species of flowing water; beautiful demoiselle (Calopteryx virgo), golden-ringed dragonfly (Cordulegaster boltonii) and keeled skimmer (Orthetrum coerulescens) appeared in droves across the hillsides throughout the valley, including good numbers in Hardknott Forest. Golden-ringed were regular garden visitors and keeled skimmers were seen in the Newfield Inn beer garden on several occasions. Both of these species are generally upland species, preferring acidic streams of which the Duddon has plenty. Four spotted chaser (Libellula quadrimaculata), common blue damselfly (Enallagma cyathigerum) and blue-tailed damselfly (Ischnura elegans) were also seen frequently around this time, though preferring standing water rather than streams. Particular hotspots were found at Black Allens beneath Seathwaite Tarn, Mosedale (worth visiting (carefully!) for the bog communities) and Holehouse Reservoir, though in honesty you’d have struggled not to have seen at least a few wherever you chose to go.

Beautiful demoiselle (male)

The heat wave in late May/June gave these species plenty of opportunities to flex their wings but unfortunately did lead to the temporary drying out of the bogs at Nettleslack and numerous other ponds and streams through the valley.

The next species to be spotted wasn’t until early July, with emperor dragonflies (Anax imperator) at Stickle Tarn. These are our largest species of dragonfly by most metrics, but the prize for longest goes to the female golden-ringed dragonfly who wins it thanks to the length of their ovipositor. Emerald damselflies (Lestes sponsa) were also first spotted here, and in the numerous tarns across the aptly named Tarn Hill, but subsequently were recorded all the way up the valley in the upland pools.

Emerald damselfly

Southern hawker (Aeshna cyanea) made their first appearance in early August at one of the very few ponds in the valley bottom, and shorty after appeared at Stickle Tarn too. This is typically a lowland species and was confined to the Southern half of the valley from my sightings. Common darter (Sympetrum striolatum) also made a few appearances in the valley bottom, in the far South at Fox Crags Tarn and a few individuals as far up the valley as Nettleslack; one of which was photographed meeting its grizzly end at the hands of a four-spotted orb spider.

A Common darter succumbing to a four-spotted orb weaver spider

August marked a clear changing of the guard with the spring species dropping off (though a golden-ringed dragonfly was seen as late as September) and the arrival of moorland hawkers (or the better name of ‘sedge darner’) (Aeshna juncea) and black darters (Sympetrum danae); the latter holding the mantle of UK’s smallest dragonfly. These species, along with emerald damselflies, took the valley by storm with particular hotspots at Stickle Tarn, Fox Crags Tarn, Nettleslack Bog and Peathill Crag on the edge of Hardknott Forest. It’s safe to assume any of the peat bogs in the Upper Duddon Landscape Recovery Project would be ideal habitat for these upland specialists. The final species recorded in the valley, bringing the total to 9 dragonflies and 5 damselflies, was a pair of migrant hawkers (Aeshna mixta) near Wallabarrow. Their arrival seemed to align with a spell of particularly poor weather, so they may have spread further up the valley if the gods had been on their side.

Black darter (male) covered in morning dew

My final record for the year was a common darter at Nettleslack bog at the end of September, when the spell of poor weather seemed terminal.

As mentioned previously, climate change poses a real risk to odonata. The increase in frequency and intensity of storms prevents them flying or foraging, and prolonged dry spells risks essential bog pools drying out early in the season. Upland species such as common hawker and black darter are particularly at risk from this latter threat, and so projects such as the Upper Duddon Landscape Recovery project will be vital in ensuring these peat bog habitats remain viable and in good condition. Hardknott Forest provides fantastic, sheltered foraging habitats, particularly for species favouring acidic, running water such keeled skimmers, golden-ringed dragonfly and beautiful demoiselles. Expanding scrub and native woodland cover, and installation of ‘leaky dams’ will be perfect for these species. Another effect of the changing climate is the expansion of the ranges of several species. Broad bodied chasers are a relatively recent colonist in Cumbria but have seen a massive expansion over the last few years (though I don’t believe they’ve made it into the Duddon as yet), and banded demoiselle (Calopteryx splendens) is showing a similar pattern; this is being explored in an upcoming article in a publication by the Carlisle Natural History Society, written by the county recorder. Several other species found elsewhere in Cumbria or in neighbouring counties could very well be recorded in the valley in the coming years.

Charities such as the British Dragonfly Society undertake numerous projects across the UK to manage habitats for these species, and the Cumbria Wildlife Trust have been instrumental in ensuring the survival of one of our rarest species, the white-faced darter (Leucorrhinia dubia), at several of their reserves. 2023 was an exciting year for this species, with several sightings of individuals a significant distance from their few strongholds, suggesting the potential of expansion to new sites. One of these sightings was close enough to the Duddon Valley to hint at the possibility we might one day see these species in Hardknott Forest or the wider Upper Duddon.

Dragonfly and Damselfly Spotting Tips

• Choose a warm, still day to look for dragonflies and damselflies.

• Mid-morning to early-afternoon is the ideal time to see dragonflies in flight at their most active, but early-morning you may find them roosting in vegetation near ponds.

• Take a camera and a pair of binoculars to help with identification.

• Remember different species are on the wing at different times of the year, and favour different habitats. Identification Help - British Dragonfly Society (british-dragonflies.org.uk) is a fantastic resource to learn how to identify species, and their habitat preferences.

• Make sure to record your sightings – I like iRecord, but there are numerous ways to do this.

• The Cumbria Biodiversity Data Centre has produced a fantastic atlas of dragonfly and damselfly distribution in Cumbria - Cumbria Dragonfly Atlas - Cumbria Biodiversity Data Centre (cbdc.org.uk)

• Some of the Duddon Hotspots include Hardknott Forest, Nettleslack Bog (stick to the boardwalks!), Mosedale and Stickle Tarn.