Place names at Hardknott

"THE PLACE NAMES OF HARDKNOTT" by Tasmin Fletcher, Project Assistant, October 2020.

"THE PLACE NAMES OF HARDKNOTT" by Tasmin Fletcher, Project Assistant, October 2020.

Looking across a map, as many of us do when out walking, we often take for granted the array of descriptive and informative names scattered across the paper. Given to the landscape by our predecessors, they mark out features that were worthy of note, be this for habitation, food, medicine or safety. By continuing to use these names today, we gain an insight into the past, and make the lives of these people tangible again, providing a connection to the landscape which has been lost for many.

Although a lot of place names are easily decipherable today (think Long Crag or Great Wood at Hardknott), I think the majority of names, whether for human features or to describe the landscape itself, are often incomprehensible in modern times and can seem nonsensical or downright bizarre. Over time, we have become less rooted to landscape in our everyday lives and experience it on a much greater scale, so marking out the intricacies of a small patch of land is less important. Language evolves and meanings are lost. Obviously there are exceptions to this for those whose lives continue to be focused around a specific area, such as farmers or land managers. The key to place name longevity is in their continued relevance to the people of the landscape.

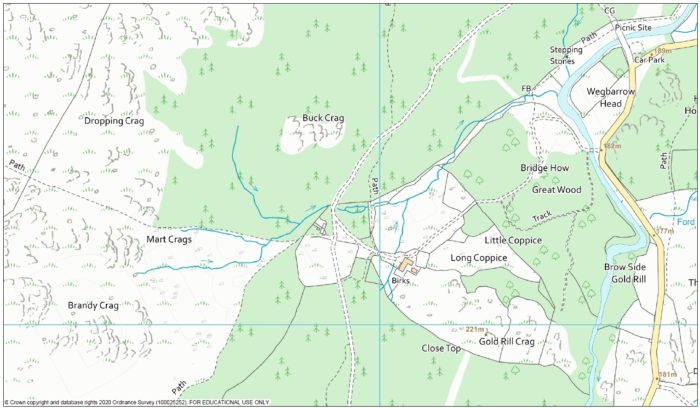

Through the place names at Hardknott we can build a picture of what the site was like in the past. For example, we have the main settlements of Grassguards and Hinning House, both of which refer to enclosures of land (‘guards’ being a dialect term coming from the Old Norse garðr and ‘hinning’ from the word hegning in Old English). We also have Swinsty How, (the hill of the pig sty), as well as Long Coppice and Little Coppice next to Great Wood, where we know the traditional practice of coppicing would have occurred. To the north of the site we also find Skelly Crags, which may come from the Old Norse skáli, meaning shieling (this is also where we get Skelwith from). Although there is no archeological evidence immediately next to the crags, there is evidence of shielings in other parts of the site, making this not an unlikely suggestion.

Transportation routes were also of note, for example Kepple Crag comes from the word capel, meaning horse, likely referring to the nearby packhorse route. Interestingly, there is also a mirroring Kepple Crag on the Eskdale side just a few kilometers away on the path between the two valleys. Bridge How refers to the nearby crossing at Birks Bridge, which would have been an important landmark before the building of the new bridge at Froth Pot (itself referring to the shallower water at this point, ‘froth’ possibly coming from the Old Norse word vath meaning ford).

When did a pine marten last inhabit Mart Crag?

We also get a picture of the local wildlife, particularly species which could either be helpful (e.g. for food) or harmful (e.g. predators). By the river we find Troutal, ‘the trout pool’, after the deep pool found behind the farm, which historically would have been a spot for trout and salmon fishing. Harter Fell is named after the hart (female red deer), and Buck Crag after the male roe deer. We still see both red and roe deer at Hardknott today. In the same area we find Mart Crag, referring to the pine marten which was hunted for its fur and was known at the ‘sweet mart’ to distinguish it from the polecat, or ‘foul mart’, known for its unpleasant smell.

A recent photograph of Cat Bield

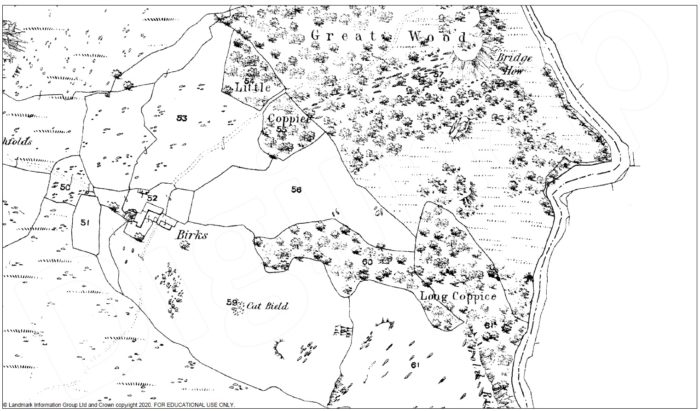

My personal favourite place name has to be Cat Bield, located in a field near Birks. Denoting the location of a wildcat den in amongst a rocky outcrop, this name is only marked on maps up until the 19th century, when the wildcat was hunted to extinction in Cumbria. Visiting it today, it’s clear that this would have been a prime location for a wildcat to rear its young, and its proximity to the adjacent farmstead shows that people lived alongside these animals in the past.

The settlement of Birks of course relates to the native birch trees which are again coming to dominate the area. Other plant references include Rowantree How and Gold Rill Crag – the crag of the marsh marigolds. The name is probably highlighting the attractive colour of the flowers rather than identifying them for any medicinal value, but also serves to tell us that this crag is probably a fairly boggy place (as visitors to this area can attest!).

The majority of other place names on the site describe geomorphological features. As well as the ones already mentioned, we have Dropping Crag (the crag that falls away steeply), Pike How (the pointed hill), Crook Crags (the crags on a bend/with a bend), Basin Barrow (bowl-shaped hill) and Saddlebacked How (the saddle-shaped hill).

Castle How probably refers to the shape of the hill itself, rather than the presence of any historical fortification, however building remains around the hill suggest the area was previously inhabited. The word ‘how’ comes from the Old Norse haugr, and describes a small hill that is often free-standing and relatively round and steep. The area between the car park and Birks Bridge, known as Wegbarrow Head, could be referring to a prominent bend in the River Duddon (‘weg’ possibly coming from the Old Norse vík).

Then we have some more curious ones for which origins are uncertain. These include the River Duddon itself (potentially meaning ‘black valley’ but the name is obscure), as well as Brandy Crag and Fickle Crag. The former may refer to a smugglers’ cache off the nearby packhorse route but this is unclear, whereas the latter seems to have no obvious reasoning that I could find, although locally it is sometimes known as ‘Fiddle Crag’ so perhaps there’s a story in that somewhere… If anyone reading this can enlighten me I would be very interested to know!

Overall, I think we really gain something from an understanding of place names. Not only can we benefit from an increased appreciation of the environment and past people’s lives, but they often challenge our assumptions about how landscapes appear now, connecting us beyond living memory to how they looked in the past. By extension of this, it also opens our minds to how it may look different again in the future, and allows us to embrace changes as a part of evolution of the landscape.

Further reading

A Dictionary of Lake District Place Names by Diana Whaley

Out of the Forest: The Natural World and Place names of Cumbria by Robert Gambles

Please contact us with any other place name information, either for Hardknott Forest itself, or the wider Duddon Valley.

T.I.Fletcher@leeds.ac.uk